There was a time smoking seemed to be healthy.

Kategorie: Unzugeordnet

Rare and Fascinating Historical Photos #4 — Sir Winston Churchill in a swimsuit; 1922.

No sports, but swimming 😉

The “Ebony Venus” and the “Bronze Apollo" – Josephine Baker and the Russian-born French ballet legend, Serge Lifar, on the Lido beach in Venice, 1930s. Ms. Baker talked about this day in “Josephine,“ the biography she wrote with her former husband, Jo Bouillon, which was published in 1976, one year after her death.

“We had had a wonderful time together on the beach in Venice during my Italian tour. I loved to hear Serge speak. He was more entertaining than all the pigeons in St. Mark’s Square. I’d like to have been Picasso in order to sketch him… Actually, he knew Picasso, as well as those who had made me the “ebony Venus” and named him the “bronze Apollo.” Paris had welcomed him from the East two years before I arrived from the West. There on the sun-drenched sand, intoxicated with the sheer joy of motion, we danced. What a curious pas de deux – the star dancer of the Paris Opera and a colored entertainer swaying together in bathing suits on the Lido beach.” Photo: Hotel des Ventes, Geneve.

Beach Life

We have a nice sunny weekend ahead. Some impressions of interbellum beach life will follow.

Tauentzien girls (lower class of prostitutes), Berlin 1920s.

Berlin in the 1920s had a very interesting and confusing legal stance on prostitution. Left-over laws from the reign of Friederich II did not allow for legally sanctioned brothel quarters within city limits, and yet individual female and male prostitution was to be carried out “under government surveillance" – in essence, it was permitted on a technicality despite being officially unlawful. “Whoring was, through the Wilhelmian era, alternately tolerated, then banned, then yet again ‘placed under surveillance.’ No matter what was decreed, however, prostitutes and the citizenry who engaged their services always found ingenious ways to circumvent the murky codes. Only two sanctions were consistent: 1. Berlin refused to allot a legal district for the practice of harlotry – the ‘Mediterranean’ solution, and 2. public solicitation for sex was strictly prohibited” (Gordon, Voluptuous Panic).

So, in essence a prostitute could ply his or her trade anywhere in the city as long as he or she did not verbally reveal her profession. Hence, an elaborate cosmopolitan code of dress and gesture developed in the Berlin demimonde through which sellers advertised their wares to buyers: “Customers could recognize the compliant goods instantly by their characteristic packaging. In other words, whores would promote themselves by looking like whores” (Gordon, Voluptuous Panic). A fascinating paradox, because of course looking that way made your trade obvious to law enforcement officials and yet they there was little they could do about it.

However, “the problem, unfortunately, became acute in the Weimar period when prostitute fashion was widely imitated by Berlin’s most virtuous females. For instance, one historical badge of shame for Stricht-violators, short-cropped hair, became the common emblem of the Tauentziengirl (above) at least for a year or two. Then in 1923, the short pageboy coif, or Bubikopf, achieved universal popularity as the stylish cut for trendy Berlinerinnen. Prostitutes had to change and update their provocative attire constantly in order to retain a legal means of solicitation” (Gordon, Voluptuous Panic).

Louise Brooks remembers her time in Berlin in “Lulu”

»At the Eden Hotel, where I lived in Berlin, the café bar was lined with the higher-priced trollops. The economy girls walked the street outside. On the corner stood the girls in boots, advertising flagellation. Actors’ agents pimped for the ladies in luxury apartments in the Bavarian Quarter. Race-track touts at the Hoppegarten arranged orgies for groups of sportsmen. The nightclub, Eldorado, displayed an enticing line of homosexuals dressed as women. At the Maly, there was a choice of feminine or collar-and-tie lesbians. Collective lust roared unashamed at the theatre.«

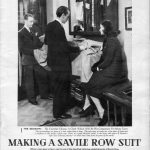

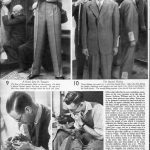

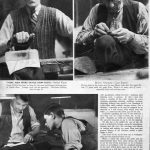

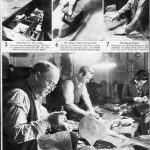

Savile Row, 1939

This article from England’s defunct Picture Post magazine depicts the process of ordering and making a suit at Williams, Sullivan, & Co., a firm that occupied 12 Savile Row at the time of publication in 1939. Today the building houses Chittleborough and Morgan, formerly of Tommy Nutters’ shop, and the Scabal flagship store. (Check out a recent Chittleborough and Morgan suit in navy seersucker at Permanent Style.) Picture Post was a photo-heavy publication not unlike LIFE, and this piece gave the reader a glimpse into the clubby atmosphere of a tailor’s shop (for the customers, at least; the article mentions sewing girls making £3 a week—around £165 today).

“Even if you cannot tell an Englishman abroad by anything else, you can tell him by his suit. The suit may be old, it may have done a dozen years’ service, but its cut and the way it hangs on his body identify the owner as an Englishman.”

-Pete

What a fantastic post, thanks!

Found via dieselpunk.org

Vintage aerobatics material. Fascinating, mad as ever. What can I say: the flying circus.

The Royal Wedding (1923)

26. April 1923